The woman is reading a book on her way to class, walks into a room, takes off her staid outfit and begins dancing around. Near the end of the ad the woman peeks out of the room and says "쉿! 지금은 수업중입니다." You can watch the video for yourself here. This is the point I made on my original post:

Given the tagline at the end of the 30-second TV spot---즐기면서 배우는 영어회화센터---the gist is that with WSI you can have fun and learn English, too. Nothing wrong with that, but if that's an acceptable angle, perhaps foreign teachers might be forgiven for wanting to have fun and teach English as well.

I'm not saying the commercial is obscene or anything, or that it's upsetting my Victorian sensibilities. I was just struck by that angle when you think about the resentment and cockblocking foreign guys sometimes deal with in Korean clubs, and the netizen anger at foreign teachers who hang out with Korean women. But, yes, one thing doesn't have to do with the other, and the marketing department of WSI is in no way affiliated with or responsible for the reader comments at the bottom of a news article. Interestingly, and perhaps revealingly, there are no foreign-looking men in the commercial, and though you don't need foreigners or native speakers to use English, their absence here is what drew my attention to the contrast in attitudes in the first place. English here is used to represent youth, fun, and a cosmopolitan sensibility, though it's curious to see it advertised without any indication of those most associated with using it.

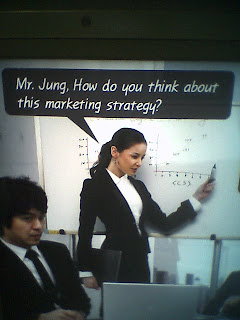

But then again it's common to divorce the language from its speakers here, as practically all English-language material here has errors that render the piece anywhere from awkward to incomprehensible. Another advertisement for an English school has been making its way around the internet; actually, looking for it two weeks ago is what put me on the trail of the above WSI commercial in the first place. The esteemed Mithridates on his Page F30 blog snapped a few pictures of it in the subway station; here's one:

Confusing "How do you think about" with "What do you think about" is a common error, as is inconsistent capitalization. Every time I see incorrect English on signs, in books, on television, or wherever, I have two immediate reactions. The first is to shake my head at the misuse of my native language because, even though the errors were probably not intentional or malicious, their use demonstrates an indifference to doing it right. My second reaction is to wonder why on earth companies would spend thousands of dollars and hundreds of man-hours on an ad campaign, but not take two seconds to see if the language they use, and in this case the product they're advertising, is correct. I'll stop you right there and save you the trouble of telling me it doesn't happen only in South Korea or only in Asia, but the chronic inability to get it right is mind-boggling. In a Korea Times article last week on an English-language government website that's filled to the brim with errors, Kyung Hee University law professor Joseph Harte sums it up nicely:

Reviewing overall content, Harte said he had found numerous grammar, usage, punctuation, spelling and even typographical errors. ``Unfortunately, this suggests either carelessness or arrogance,'' he said. ``It also leads users to question not only the site's usefulness to its intended audience, but also, unfortunately, its reliability as well.''

He's talking about a particular website, and not bad English as a whole, but "suggests either carelessness or arrogance" is an appropriate explanation. I can't tell you how many awkward or incorrect pieces of English I've seen on English exams at school, even on the extremely important mid-terms and finals. Either the teachers writing the questions don't care about misusing the language, or more likely, they're so convinced of their abilities that they don't feel any need to ask me to proofread.

All this undercuts the stereotype that out-of-touch academics love to use to characterize Asian learners of English, namely that they're relative experts at grammar and reading, but struggle simply with speaking, a struggle that comes from the lack of emphasis on speaking in class and with a fear of making mistakes and losing face. Were that true we probably wouldn't find errors and sloppy mistakes on a high percentage of signs, posters, and plaques, and in far too many newspapers, magazines, commercials, and English textbooks. However this fear of being wrong doesn't seem to extend to creating signs with awkward English that end up posted all over town.

Of course, English isn't a language in Korea; it's a subject, a commodoty, a symbol. In this case the English is secondary. The attractive woman---who may or may not even be an English-speaker given the prevalance of Eastern European models here---is embarrassing the disheveled older man, telling us that if you don't study English you not only won't understand what's happening at the meeting, but you'll look like an idiot in front of hot white women.

And there are other things going on here, too. Mr. Jung's reaction---Why is she looking and talking at me???---would fit right into any of our students head during a class; in any classroom in the world, for that matter. The other men are clearly out of it and not paying attention, though you have to wonder whether they'd carry themselves the same way if not listening to a presentation by a foreigner, a woman, or a foreign woman.

And speaking of different reactions to foreigners and foreign women, we of course are familiar with the way we're perceived and treated in the English classroom, but commentor Sonagi drew attention to some young women making the V-sign in a picture with Secretary of State Hilary Clinton during her visit to Seoul last month.

10 comments:

Grammatically incorrect use of English in official or commercial applications always makes me cringe, too, for pretty much the exact same reasons. And, with spell checking built into word processors and even operating systems, spelling errors do nothing more than to affirm my suspicion that there really is a great deal of apathy towards .

Your example of mistakes (or, as you point out, are they? can we really call them mistakes if they don't make an honest best-effort to avoid errors?) in school exams struck me in particular, because I attended middle school in Korea (not an international school) and saw plenty of mistakes in English midterm/final exams as well. Now, our school didn't have a native speaker on staff, but the head of the English department, an older woman who almost seemed to cherish me as a teacher's pet was always reasonable enough to correct the mistakes in grading when I pointed them out. (In retrospect, I wonder why I never took advantage of this to cover up some terribly embarrassing mistakes I made on a couple exams. =P) I can only hope that the teachers at your school are just as willing to swallow their pride for the sake of their students.

There's a question I've always wondered about and wanted to discuss regarding the efficacy and justification for strongly preferring native speakers for English teaching positions (and I think it's pretty clear that this is just a political correct euphemism for "people who look like native speakers"). I think there might be some issues there that might arise from cultural biases and expectations from both sides (students and teachers), but not being an educator or a student growing up in Korea, I can't really comment on my under-developed thoughts.

I've only just recently stumbled upon this treasure trove of blogs written by English teachers and others living in Korea, so maybe I'll come across a post that realizes these musings better. I'll take another swing at it then.

P.S. Sorry about the multiple comment mess.

Thanks for the visit and the comment.

Regarding the last point about native speakers, this is a huge topic that could go round and round in circles all day. I'm not a person who believes being a native speaker automatically makes you a capable teacher. Seems like people in charge here are also realizing that, as there are plans to bring in non-native speakers from countries that have English as an official language (India, for example), provided they have the proper qualifications.

For the record, I don't consider "qualifications" as . . . well, qualifications of a good teacher. A person with, say, teacher certification back home or a MA in TESOL might absolutely flounder in a foreign environment like Korea, regardless of the quality of their training. Likewise, our Korean colleagues have been exposed to English their whole lives and have gone to university---and have had professional development opportunities since then---but our experiences tell us that their knowledge of English sometimes doesn't extend beyond what the CD-ROM is telling them.

Now, the rub here is that we're usually not hired to be "teachers," but rather are "native speaker assistant teachers." Can a native speaker automatically be a good teacher? No. But can a native speaker automatically be a good native speaker? Of course. (The issue of "good" native speaker, and the preference for some Englishes over others is another story).

One of the headier issues for native speakers here, should they choose to accept it, is understanding how to be a native speaker. What I mean is there are certainly cultural expectations of how NS teachers should behave (see the "English Cafe" category for example). We have to fit in to a system that, at least to read the national curriculum, is shifting its aims to communicative competence, but do so in a culture where perhaps CC is inappropriate. We have to learn the difference between English as we know it and the English SUBJECT as interpreted in Korea. Unfortunately except on some of the blogs I haven't seen much scholarship on this . . . the journals seem to favor and sympathize with non-native speaker teachers, still harping on the English Imperialism trend. And related to posts I've made about the difficulty for foreigners to comment on Korean culture, I wonder if foreign scholarship in academic journals on teaching here would even be accepted.

I agree with you that English is treated, not as a language, but as a commodity - a thing - in this country. I think that's the main obstacle to anyone actually learning it. I work at a chaebol, and I always ask my learners why they need/ want to learn English and what their favourite English-language book/poet/movie etc is. The former evokes generic and meaningless replies of: 'to talk to foreigners' or 'improve my listening skill', while the later elicits blank stares. There is no real-world application or cultural context. Paradoxically, people I meet dont want to practice English so they can talk to foreigners, they want to talk to foreigners so they can practice English. It's a ridiculous abstract concept - "speaking English well". I blogged a couple of months ago that I was really suprised that when Kim DJ accepted his Nobel Peace Prize his speech didnt consist of "Thank you everyone, I'm so happy for this chance to practice my English."

That's an interesting point that I had never thought. The idea of trying to fit your "native speaker" status, which really is just who you are, into a professional context and try to fulfill that role appropriately. I can't even really grasp what that means.

회화 was basically a buzz word for hagwons back when I was in Korea, too. I think it is a good thing that the general curriculum is moving to favor teaching CC, but reflecting on my own personal experience in Korean schools (which I hope, perhaps unrealistically, is different now less than 10 years later) my mind just reels and says, "Wait. That just doesn't work. How can you... In those classrooms.. With these teachers.. What? How?"

With regards to my concerns about seeking out native speakers, I don't think they are really addressed by finding them in countries that aren't limited to those that fit the stereotype. This is kind of a chicken and egg problem for me, and I'll wait to read more on the topic before I try to fully articulate. Suffice it to say, I just wish we could skip all the growing pains and get to the, perhaps a bit quixotic, state where a English teacher (or rather, a teacher in general) is just a teacher. A native speaker can be a teacher just like any other, to fellow teachers and to the students, and really that non-native English teachers will be just as comfortable and proficient with the language - and not just on paper. Even more, to extrapolate this to the entirety of Korean society. Because, just as if a native speaker is seen first as a foreigner and secondly as a teacher , he/she won't be able to teach most effectively, if that person is seen first as a foreigner and only secondly as a member of the population living in Korea by native Koreans, then that person will flounder as you say in the less than hospitable environment. The same can be said, of course, of how the "teacher" (in this context) views Korea and its people.

I used to expression "growing pains" earlier, and it really is a bit of a cliche, but the twinge of nationalistic/ethnic pride in me really hopes that these issues, and the many more similar related and unrelated ones, are just the growing pains of a society toward modernity. (Disclaimer: I'm purely an engineer by education and am probably misusing that term that I picked up in the one French history lecture I went to.) The alternative that these very ethno-centric(?) ideas are much more entrenched is just a little too depressing for me. It's hard for me to tell what the situation is really like over there. It's been several years since I lived there full-time and almost just as long since I've talked with any friends who live their full time. The bits of news I catch is too often.. well, not encouraging.

I always tend to rant longer than I intend to when I'm up late, so I'll just finish off by saying I've been reading your blog for a few days now and I like they long form way in which you write out your thoughts - keep it up. And, I'll definitely be making a point of heading over to the English Cafe category and see what's there.

There are a lot of issues here, but one factor I have seen first hand many times is that the Koreans/Japanese/Taiwanese hire a native English speaker who is more interested in the cash opportunity than doing the job carefully.

I knew of a case, for example, where someone was to be paid 500,000 won for x number of pages of proofreading. He decided that 500,000 at a private tutoring rate would be about ten hours (something like that; I don't recall the exact numbers). He proofread for ten hours and then stopped where he was and submitted the entire thing. Of course, that meant that the last part (about one-third, he admitted) wasn't proofread at all, but he didn't tell that to the people who paid them.

If they wanted the whole thing done right, he said, they should have paid me more (bear in mind they had made no promise it would take only ten hours, just that that's how much he thought he should put in for 500K won).

My ex is a meticulous proofreader and when she heard this (from him, like he was bragging about his quirky work ethic) she practically ripped him a new one.

I can imagine that the "How do you think" thing might also be the result of the 빠리빠리 thing where they got a native English speaker at the last minute, possibly even handling it over the phone. When even a meticulous proofreader is faced with "And what do you think of this sentence? And this sentence?" for ten or twenty times over the phone, it's easy to get crossed wires.

Proofreading is a whole 'nother story. I remember getting forwarded a webpage for a university that wanted to be turned into English. It ended up being a couple hundred of pages and the pay was a couple hundred thousand won. As you know from having to proofread Korean English, it often isn't a case of "just fixing the grammar," but having to rewrite the entire thing. Buyer beware with proofreading.

But as far as this ad---or most English in general---I'd be surprised if a native speaker were even consulted. Or if s/he were, the suggestions ignored. I know in school I was asked to clean up some awkward English on a few posters that were to go up in the halls, and after making the changes the old posters went up anyway. And when I proofread an exam last semester I found mistakes on about 1/3rd of the questions/answers. The English teacher who wrote the exam didn't like that I made so many changes, so he kept the original version.

Sonagi wrote:

I noticed the V-signs, too, and wondered if the women would have done that in a photo with Yu Myung-hwan. I don’t think the women meant deliberate disrespect. It may be that Hillary was informal with them in a way that a Korean male government minister would not be.

It's an apples and oranges kinda thing. Hillary Clinton is outside the Confucian-ish Korean hierarchy and so how Korean students behave around her could easily be different from how their behavior around Yu Myung-hwan. It's not a matter of respect or disrespect but what's appropriate and acceptable in a Korean/Asian context versus what's appropriate and acceptable in an American/Western context.

Rightly or wrongly, Koreans learn that Americans/Westerners are more casual and freer, and Hillary's speech may very well have reinforced that impression. This is, in fact, one reason why many Koreans/Japanese/Taiwanese, etc., feel a sense of relief when speaking in English with foreigners: that rigid hierarchy is lifted and they can just be.

Thanks for the link Brian – and as an aside, for that thing you emailed me too – and to return to your point about there being no foreign men in the commercial, your readers may be interested in Keiron Bailey’s 2006 journal article Marketing the eikaiwa wonderland: ideology, akogare, and gender alterity in English conversation school advertising in Japan (pdf in the first link below) about advertising for language schools in Japan, where the potential for romance with foreign male instructors and/or foreign men in general is a common and explicit motif. Of course, the contrast with Korea couldn’t be greater, although that isn’t at all to say that such things (like willingness to drink with students also) aren’t also taken into account by language school bosses when hiring teachers or by students when choosing whose course to take, as I discuss in my own post on the subject of (adult) student-teacher relationships in the second link.

http://thegrandnarrative.files.wordpress.com/2009/02/marketing-the-eikaiwa-wonderland-keiron-bailey.pdf

http://thegrandnarrative.wordpress.com/2009/02/03/sex-and-gender-in-the-korean-esl-industry-students-on-top/

Come to think of it, you seem to spend just as much time on Dave’s ESL Café as I do, so I suspect that you’ve already read the thread mentioning the article where I first found it, right? Do you remember the title of it or any of the posters in it by any chance? I forgot to save a link. Sure, I could just look again myself sorry, but the search function there is useless, and it’s no big deal really: just if you know off the top of your head. Cheers.

No idea about that thread. I did see this one where you brought up things related to Korea, and added a link abut Japan (now dead), but couldn't find anything else:

http://forums.eslcafe.com/korea/viewtopic.php?t=121042&postdays=0&postorder=asc&highlight=eikaiwa&start=15

I agree with the difficulty of proofreading. I recently volunteered to correct a few mistakes in the English subtitles for a production of Kongji Patji, and ended up spending several hours. It quickly slides into semantics, and what statements are true, which are ironic, satire, and so on.

I suppose it's easy to correct the one-liners, but it's difficult to match the plot of an entire play, etc., between the two languages. Konglish may never be completely eradicated.

Post a Comment